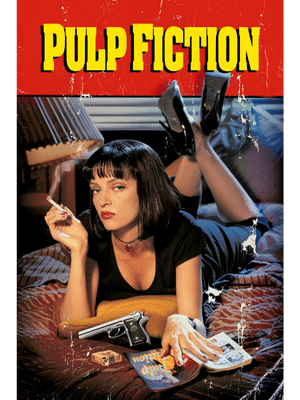

Pulp Fiction

1994, Crime/Drama, R, 2h 34m

Table of Contents

What Is Pulp Fiction About?

The lives of two mob hitmen, a boxer, a gangster and his wife, and a pair of diner bandits intertwine in four tales of violence and redemption.

Why You Should Watch Pulp Fiction

Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction is not merely a film; it’s an event. Released in 1994, it revitalized the crime genre, introduced a fresh narrative structure, and stamped Tarantino’s indelible mark on the world of cinema. More than just a pop culture phenomenon, Pulp Fiction is a dizzying medley of sharp dialogue, dark humor, and audacious storytelling that challenges conventional cinematic norms.

The film’s non-linear narrative weaves multiple tales that intersect and overlap, mirroring the pulp magazines from which the film draws its name. Tarantino and co-writer Roger Avary dive into the lives of two hitmen, a boxer, a gangster, his wife, and a pair of diner bandits, examining morality and chance amidst a backdrop of casual violence. Instead of a straightforward storyline, viewers are taken on a roller coaster of interconnected vignettes that force them to piece together the jigsaw puzzle.

A significant strength of the film lies in its dialogue. The characters don’t just converse; they deliver verbal ballets. Conversations about foot massages, European fast-food variations, or the nature of divine intervention are equally engrossing as the more overtly dramatic moments of the film. It’s this blend of the mundane with the macabre that lends Pulp Fiction its unique charm.

The ensemble cast turns in stellar performances across the board. John Travolta, in a career-reviving role as Vincent Vega, navigates the film’s world with a blend of bemusement and professionalism. Samuel L. Jackson’s portrayal of Jules Winnfield is electric, oscillating between philosophical musings and explosive rage. Uma Thurman’s Mia Wallace is alluring and unpredictable, while Bruce Willis brings a brooding intensity to the boxer, Butch Coolidge.

It’s also worth noting the film’s exploration of redemption. Amid the snappy dialogues and stylized violence, a deeper introspection about choices and their consequences runs through the narrative. Jules’s transformation from cold-blooded hitman to a man seeking redemption underlines the film’s central question: Can individuals, even those deeply entrenched in a life of crime, find salvation?

Pulp Fiction is an audacious masterpiece that broke the mold of 1990s cinema. It’s a film that defies categorization, blending elements of crime, dark comedy, and drama into a postmodern extravaganza. It’s not just a movie to be watched, but an experience to be felt, discussed, and remembered. Whether as a study in filmmaking, a source of iconic pop culture moments, or a deeply philosophical narrative about fate and choice, Pulp Fiction firmly stands the test of time.

The Theme of Pulp Fiction

Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction transcends its stylish, nonlinear façade to delve into a narrative replete with thematic depth. Central to the film is the theme of redemption, most notably embodied by Jules Winnfield. After a miraculous escape from bullets, he sees it as a divine intervention, leading him to abandon his criminal life. This spiritual transformation casts Ezekiel 25:17, a verse he often quotes, in a new light, shifting from a chilling prelude to killings to a profound reflection on his life’s path.

Alongside this, the film dances on the lines of moral ambiguity, suggesting a nuanced honor code even in the criminal underworld. Despite the backdrop of crime, characters like Butch display surprising honor, exemplified when he saves Marsellus from danger, an act contrasting their earlier enmity. Yet, the film also emphasizes the randomness of life. From Vincent’s unexpected death to the coincidental pawnshop scene, life’s unpredictability is starkly highlighted. But through characters like Jules, Tarantino posits that amidst this chaos, individuals can seek and find purpose.

A trademark juxtaposition in Pulp Fiction is the interweaving of mundane conversations with scenes of extreme tension or violence. This contrast magnifies the film’s commentary on how ordinary moments can coexist with life’s extremes. Adding to this is the film’s nonlinear storytelling, mirroring the fluidity of memory and emphasizing the interconnected narratives of its characters. The hyperreal, sometimes humorously portrayed violence, serves both as homage to pulp novels and as a statement on the desensitization of audiences to brutality.

Furthermore, the film’s frequent pop culture references not only ground it in a specific era but suggest that characters, like modern society, often interpret their realities through media and pop culture lenses. In essence, the power of Pulp Fiction lies not just in its stylistic brilliance but in its exploration of themes like morality, chance, and the myriad unpredictable facets of life.

The Cinematography of Pulp Fiction

Pulp Fiction showcases a distinct and innovative approach to cinematography that has become emblematic of Tarantino’s style. The film, known for its nonlinear narrative, utilizes cinematography to bolster its fragmented storyline and emphasize its eclectic mix of genres.

One of the film’s most iconic shots is the “trunk shot,” where the camera is placed inside the trunk of a car, looking up at the characters as they open it. This shot, used multiple times in the film, provides a unique perspective and adds an element of intrigue, encapsulating the impending sense of danger or tension.

The dance scene at Jack Rabbit Slim’s between Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) and Vincent Vega (John Travolta) is shot with smooth tracking and steady shots, capturing their moves and the ambiance of the retro diner. This scene, bathed in neon lights, utilizes long takes to maintain the flow of the dance and immerse the viewer in the moment.

Throughout the film, Sekuła employs a combination of steady close-ups and medium shots during dialogue-heavy sequences. These shots are punctuated by swift, deliberate camera movements, often corresponding with sudden bursts of violence or tension, mirroring the unpredictable nature of the narrative.

The use of extreme close-ups, especially during intense moments—like the adrenaline shot scene or the focusing on objects like the gold watch—creates a heightened sense of urgency. The contrast between these moments and the longer, dialogue-driven shots underscores the film’s juxtaposition of mundane conversations and shocking violence.

The Soundtrack of Pulp Fiction

The soundtrack of Pulp Fiction stands as a character in its own right, playing an integral role in setting the film’s unique tone and pacing. Comprised of an eclectic mix of rock ‘n’ roll, soul, surf music, and pop tracks from various eras, it mirrors the movie’s nonlinear, patchwork narrative and enhances its vivid character portrayals.

The film opens with Dick Dale’s frenetic “Misirlou,” a surf rock classic that immediately establishes a sense of raw energy and tension. This choice is emblematic of the entire soundtrack: unexpected yet perfectly fitting. Another surf track, “Bullwinkle Part II” by The Centurions, underpins a pivotal scene, further cementing surf rock’s prominent role in the film’s soundscape.

Kool & The Gang’s “Jungle Boogie” and Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” bring soulful depth and anchor the film in a vintage ambiance, emphasizing its retro sensibilities. Similarly, Dusty Springfield’s melancholic “Son of a Preacher Man” layers emotional nuance onto Mia Wallace’s character, while Chuck Berry’s upbeat “You Never Can Tell” sets the stage for Mia and Vincent’s iconic twist contest at Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

The inclusion of dialogues as tracks, like “Royale with Cheese,” offers listeners snippets of the film’s razor-sharp and witty banter, making the soundtrack a standalone experience of the film’s essence.

In Pulp Fiction, Tarantino masterfully curates a soundscape that isn’t just background noise. It’s a central pulse, driving character development and narrative twists, and has since become as iconic as the film itself. The soundtrack is a testament to the power of music in cinematic storytelling.

The Cast of Pulp Fiction

- John Travolta as Vincent Vega – A hitman working for Marcellus Wallace.

- Samuel L. Jackson as Jules Winnfield – Vincent’s partner and also a hitman working for Marcellus.

- Uma Thurman as Mia Wallace – Marcellus’ wife who Vincent takes out for a night on the town.

- Harvey Keitel as Winston Wolf – A problem solver who is called in to clean up a messy situation.

- Tim Roth as Pumpkin – One of the holdup men who tries to rob Vincent and Jules in a cafe.

- Amanda Plummer as Honey Bunny – Pumpkin’s girlfriend and accomplice in the cafe holdup.

- Bruce Willis as Butch Coolidge – A boxer who is supposed to throw a fight but ends up double-crossing Marcellus.

- Maria de Medeiros as Fabienne – Butch’s girlfriend.

- Ving Rhames as Marcellus Wallace – A powerful gangster and the employer of Vincent and Jules.

- Eric Stoltz as Lance – A drug dealer who sells Vincent and Mia their heroin.

- Rosanna Arquette as Jody – Lance’s girlfriend.

- Christopher Walken as Captain Koons – A former soldier who delivers a watch to Butch.

The Filmmakers of Pulp Fiction

- Director and Co-Writer: Quentin Jerome Tarantino

- Producer: Lawrence Bender

- Cinematography: Andrzej Sekula

- Editor: Sally Menke

Big Kahuna Burger

Inspiration

The Big Kahuna Burger

More About Pulp Fiction

Pulp Fiction was primarily filmed in the Los Angeles area of California. Various iconic scenes from the movie were shot at specific locations around the city. For example:

- The diner scenes at the beginning and end of the movie were filmed at the Hawthorne Grill in Hawthorne, California.

- The pawn shop scenes were filmed in Atwater Village, Los Angeles.

- Butch’s apartment is in North Hollywood.

- Mia and Vincent’s twist contest took place at the now-defunct Jack Rabbit Slim’s, which was constructed inside an old bowling alley in Glendale.

- Marcellus Wallace’s bar was the now-closed Club Ed in Lancaster, California.

These are just a few examples. As is common with movies, various scenes can be shot at different locations throughout a city or even in multiple cities, but Los Angeles was the primary backdrop for Pulp Fiction